Travesia corporal

Encuentros con mujeres migrantes

Coordina: Tamara Cubas

A lo largo de una travesía impulsada por una fuerte necesidad de dejar un origen conflictivo para arribar a un destino deseado, anhelado, fantaseado, imaginado, como un lugar de salvación, la mujer migrante se enfrenta a condiciones muchas veces terribles y las historias de sus fracasos son nefastas y bien conocidas.

Proponemos un espacio de encuentro con mujeres migrantes para trabajar sobre el poder de éstas, en dejar un origen y construir un nuevo destino. Su capacidad para aventurarse a lo desconocido y arriesgarse a todo lo que pueda acontecer. Su resiliencia y estrategias de supervivencia.

En una experiencia de travesía la capacidad de diseñar estrategias y rearmar elementos de mundos se desarrolla pues de ello depende nuestra supervivencia. Asumimos esta experiencia como una musculatura poderosa desarrollada por estas mujeres.

A través de ejercicios creativos y acciones físicas se procurara traducir y trasladar esas experiencias de vida en produccion sensible en el presente. Alejándose de cualquier estrategia de excavación de los sucesos vividos, estos ejercicios pretenden accionar esa musculatura adquirida en la experiencia personal.

Estimamos que estos procedimientos pueden también colaborar en sus procesos de inserción en los nuevos territorios que habitan. Es en el cuerpo donde están alojadas esas experiencias, es desde el cuerpo en acción desde donde se activa el tránsito para lidiar con el lugar al cual arriban.

Este taller está destinado a mujeres que han realizado una travesía por tierra o por mar. Mujeres que solas o con sus crías hayan lidiado con las batallas que toda travesía nos somete.

El encuentro culmina con una formulación en espacio-tiempo realizada en conjunto a modo de cartografía individual y colectiva

Encuentros

Chicago. Encuentro con migrantes mexicanas en Chicago

By Irene Hsiao / Chicago Reader

Tamara Cubas honors women who cross borders alone

In a year of minimal mobility, migration is on the mind of Uruguayan choreographer and visual artist Tamara Cubas, who launched an international research process for Sculpting Silence/Womyn body (Esculpir el Silencio/Mujer cuerpo), her new work on women who cross borders alone, in Chicago

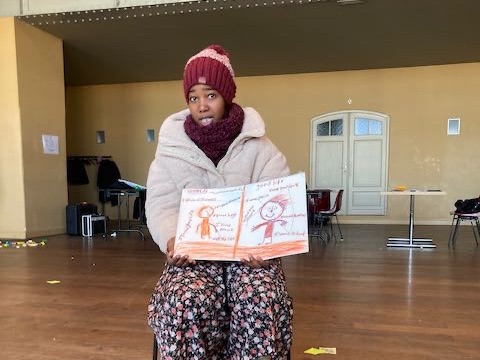

. “What interests me is potential and desire,” says Cubas. “In February, I heard a testimony by a Dominican Republic woman on her journey to the US. That particular story was dramatic and completely overwhelmed by an absolute determination she had—determination, desire, and drive.” In a residency at High Concept Labs November 6-12, Cubas conducted daily workshops with undocumented women now living in Pilsen and Little Village. Through a process of storytelling, mapmaking, drawing, writing, and movement, Cubas guided participants through a shared reconstruction of individual histories of journeying from Mexico to the United States.

“What interests me is potential and desire,” says Cubas. “In February, I heard a testimony by a Dominican Republic woman on her journey to the US. That particular story was dramatic and completely overwhelmed by an absolute determination she had—determination, desire, and drive.” In a residency at High Concept Labs November 6-12, Cubas conducted daily workshops with undocumented women now living in Pilsen and Little Village. Through a process of storytelling, mapmaking, drawing, writing, and movement, Cubas guided participants through a shared reconstruction of individual histories of journeying from Mexico to the United States.

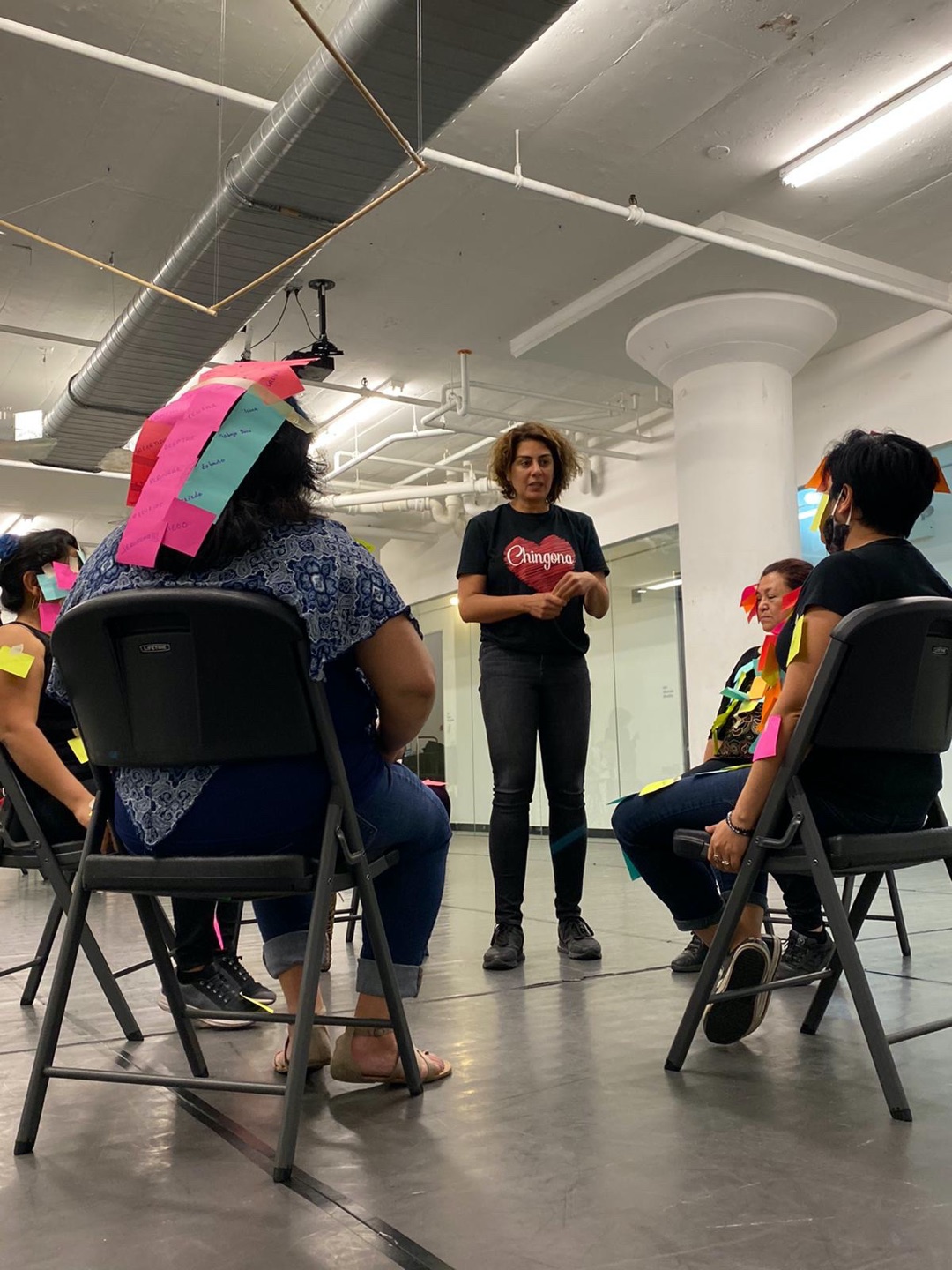

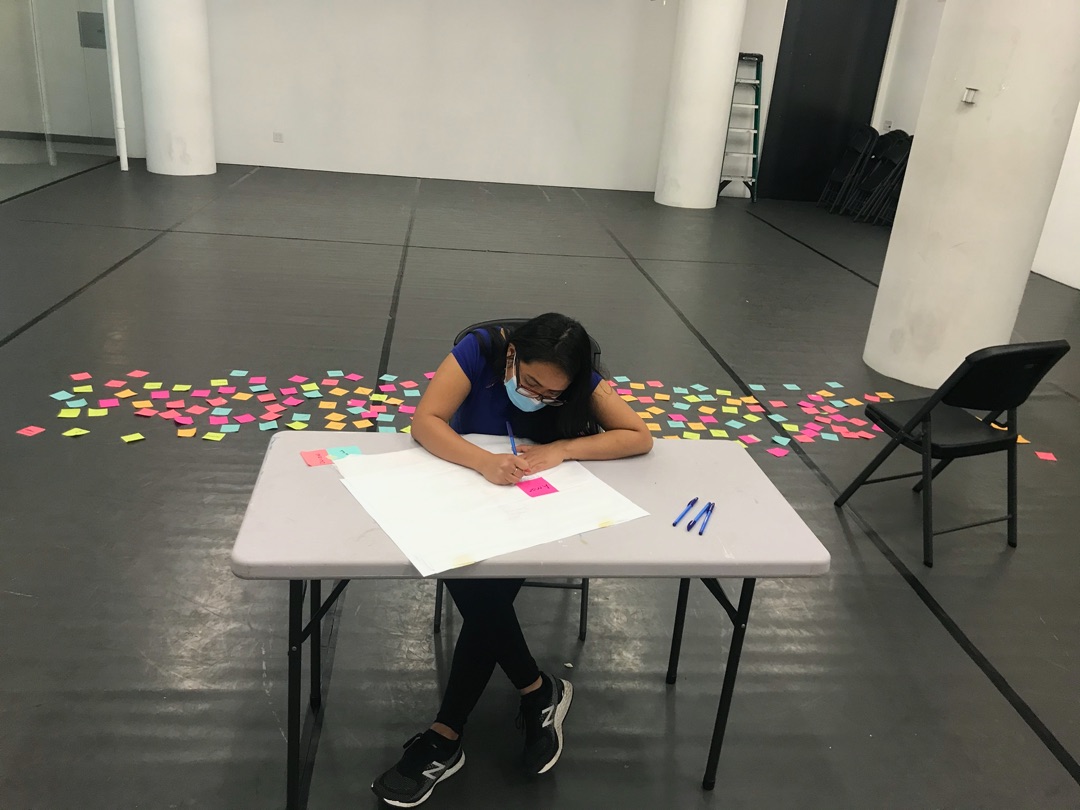

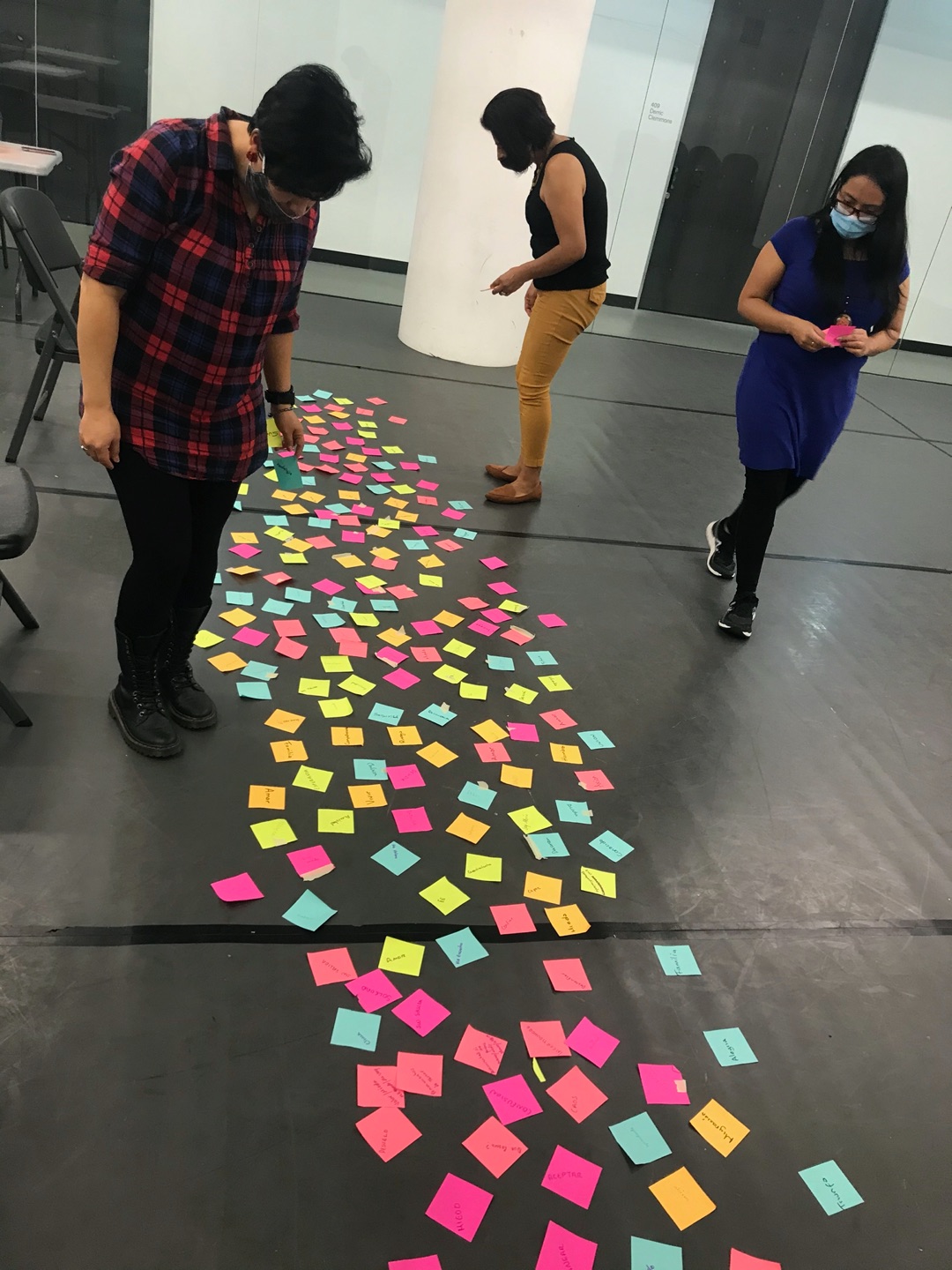

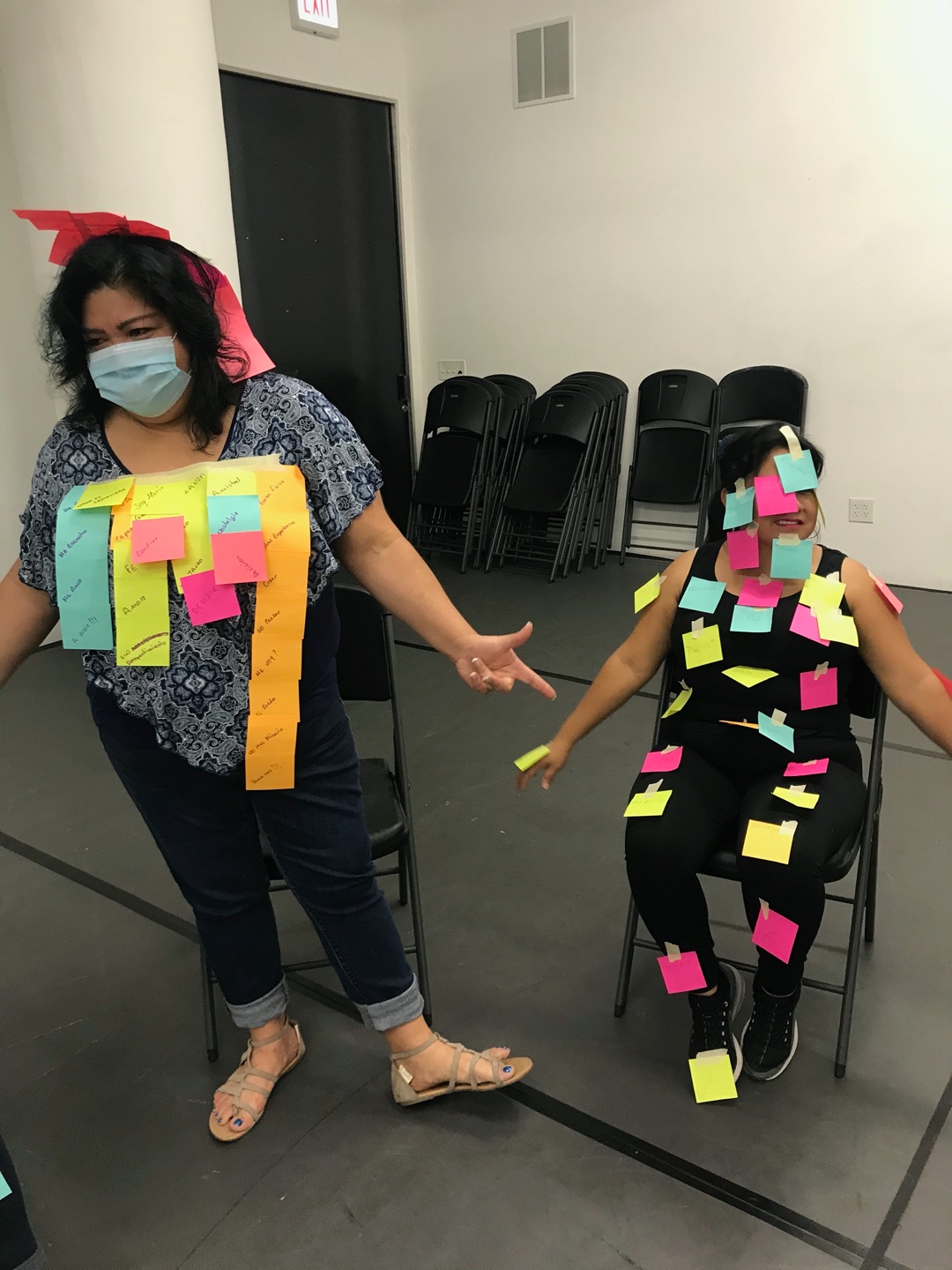

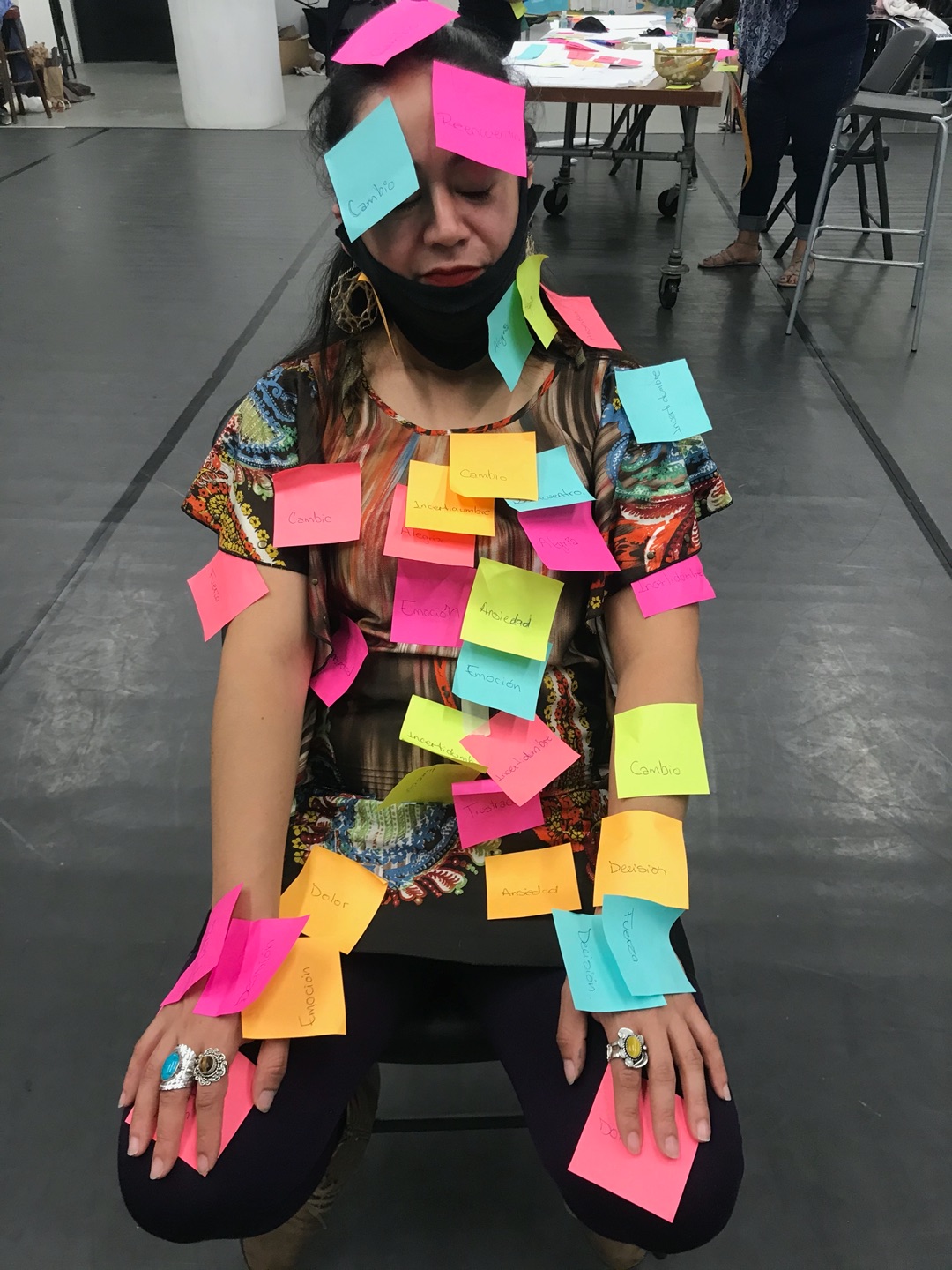

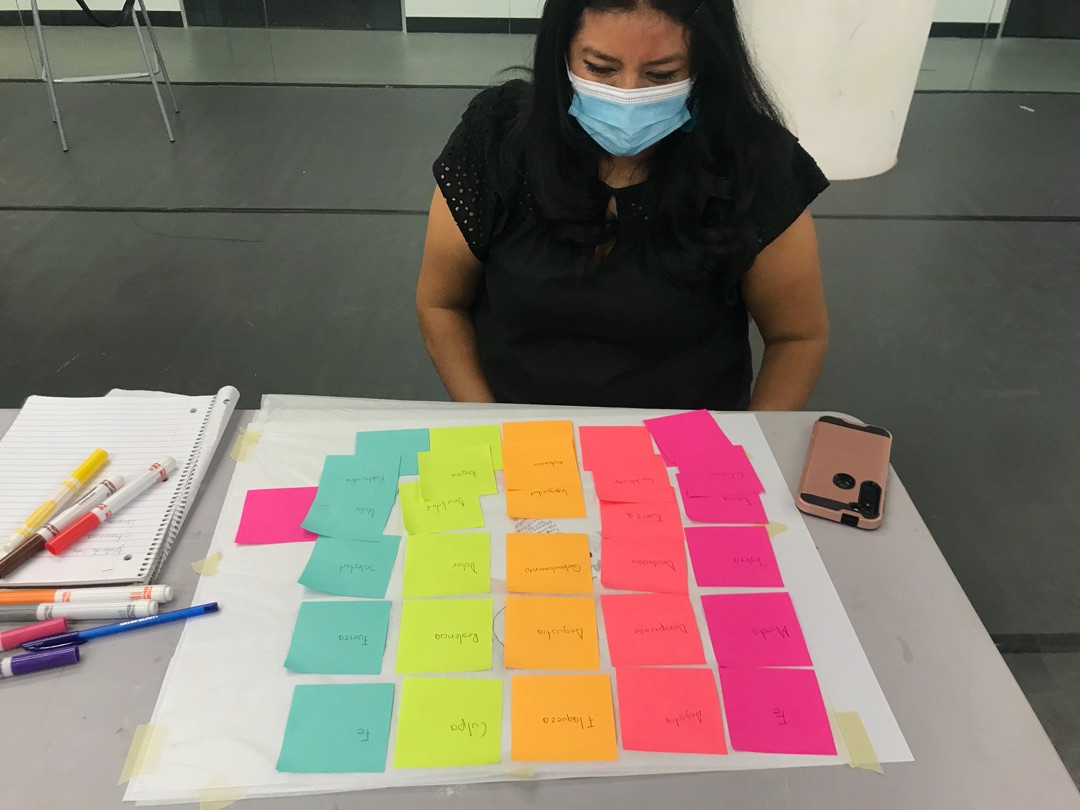

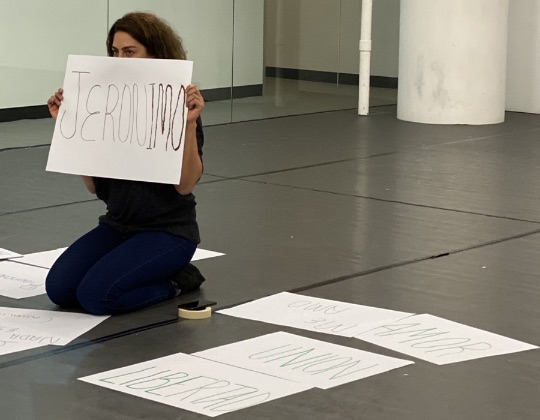

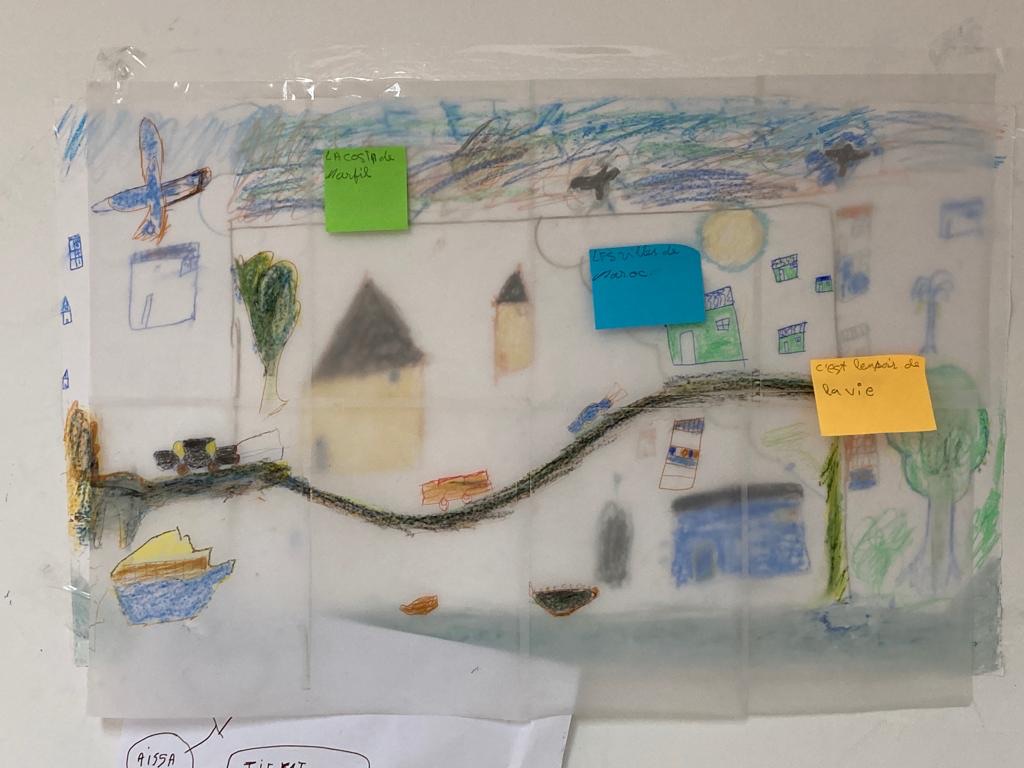

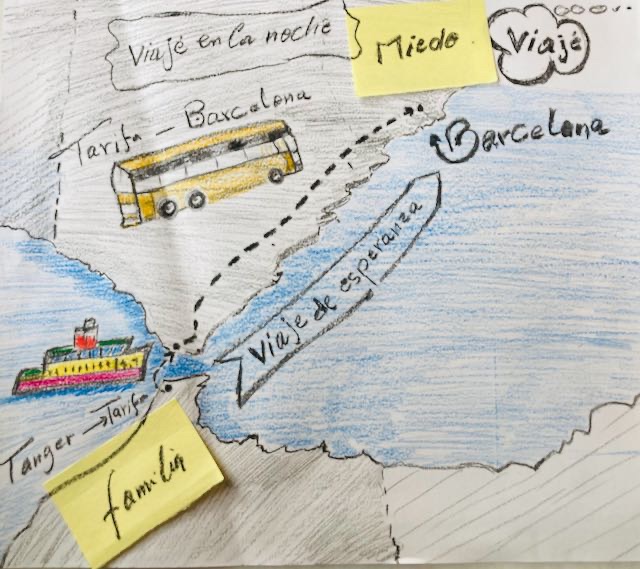

Throughout the process, they work on paper—at first, lightweight paper, the thin tissue we wrap gifts in—writing and drawing out elements of their journeys in translucent layers: the routes they took, the things they saw, the objects they brought with them. They write a letter to someone they left behind on notebook paper. They write words on fluorescent-hued sticky notes and affix each one to (in Cubas’s words) “places on the body that can carry them,” becoming colorful, scaled, feathered. They gather in a circle and speak, shedding the notes on the floor one by one, as their conversation proceeds in the style of a call-and-response. By the end of the week, they have written keywords in capital letters on broad sheets of paper that they tape to the wall: FUERZA, ALEGRÍA, SUEÑOS, PODER, AMOR, ME AMO, UNION, LIBERTAD, JERONIMO.

“For Tamara, it is important that when they start to talk, they write,” says producer Alicia Laguna. (Laguna is director of Mexico’s Teatro Línea de Sombra, which brought Amarillo, an evocative piece on illegal border crossing, to the Chicago Shakespeare Theater for the first Chicago International Latino Theater Festival in 2017.) Participants are directed to write in the first-person present, rather than the past-perfect tense, to explore their memories—and to focus especially on bodily experience. “Instead of saying, ‘I was very cold,’ she has them say instead, ‘My hair was flying,’ ‘My thighs were hardening,’” explains Laguna. “She’s trying to get them to use their bodies’ reactions as gestures. The details are in that movement. Instead of evoking feelings and sentiments, they are describing the actions of the body.”

The journeys of these women, completed decades in the past, range in length, obstacles, and terrain. One journey took a month, with three deportations. One journey took a flight, then a single day and night of walking. One woman climbed a wall. One walked three days through the desert—the perilous route dramatized in Amarillo. “The recollection has been almost instant,” notes Laguna. “They’ve all imagined or wanted to or supposed they would eventually write about it, but they didn’t know it would be now.”

“I always am sensitive to the fact that it’s not my right to reopen wounds that other people have,” she says. “I have an uncle who was disappeared, and he was never talked about. But at some point I came to understand I had an uncle who was made to disappear. And it seemed to hurt even more because he wasn’t talked about. That absence in itself is painful. And that is a natural part of my life. But is it natural to have a disappeared uncle? To have an aunt who survived ten years of torture? My entire family went into exile all over the world—is that natural? The family did not express it, but at some point when you grow up, you start to analyze it and understand that it wasn’t normal to avoid it. You look at your own life and how you try to process that, and you want to respect how another person doesn’t want to talk about it. My process creates opportunities for others to fictionalize [the past] to get it out. And hopefully in that process, my own processing happens. My family, when I had them participate in a process with me, started to acknowledge there was a disappeared uncle and they decided to take it to the government to restore his rights. So this is also the power of art. It’s complex and hurts a lot, but they made the decision to go. The family now says he deserves to be remembered.”

Entwined with trauma, the impulse to survive is the central subject of Cubas’s work. In El Dia Más Hermoso, Cubas presents a haunting video: the right hand of a woman, one finger slightly bent, gesturing in signs. The hand belongs to her aunt, Mirtha Cubas, the gestures a memory of her time as a political prisoner in solitary confinement. The prisoners, all women, created a sign-language alphabet to communicate with each other using fingers seen under the crack of the doors. “You’re in hell, you’re in shit, and the impulse for life gives you that way of communicating and connecting,” says Cubas. “That strategy to live fascinates me. She’s retelling a recurring dream that she had in prison. The only people who can read it are the people who were there.”

Now, considering global migration in Sculpting Silence/Womyn body (Esculpir el Silencio/Mujer cuerpo), Cubas is pursuing the essence of the feminine will to survive. Addressing the workshop participants at the end of the week, Cubas says, “This week has confirmed for me that, well, these women really are some chingonas. It’s affirmed the desire I had: I wanted to feed from your breasts because you are chingonas! We agreed to experiment, to attempt ways to relate, to make a document about power . . . if only more people had half your power to go and follow what they most desire! I am consummately grateful to you because of the time you dedicated to work together in this unburying of your power. And that understanding of your position is a kind of musculature. The crossing—it is not over. You are still training . . . like walking across the desert. Your desire is incredible. I ask myself—‘How do I get that power?’”

Sculpting Silence/Womyn body (Esculpir el Silencio/Mujer cuerpo) is currently scheduled for the 2021 Santiago a Mil festival in Chile. Looking to the future, Cubas says, “I want to lose myself in more than one hundred women and one hundred journeys, to arrive somewhere else. It’s about the journey—not what specifically happened on the journey—but about the force, the power. The entire time, they were free to resist and not do it. The entire time the energy was there, the spirit to live and not to succumb.” v

Note: High Concept Labs artistic director Yolanda Cesta Cursach Montilla provided Spanish translation for this interview.

https://www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/tamara-cubas-honors-women-who-cross-borders-alone/Content?oid=84300388

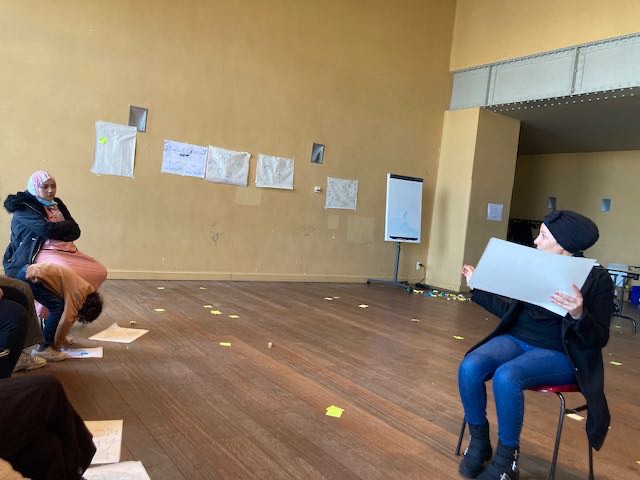

Cadiz. Encuentro con mujeres migrantes de Costa de Marfil y Marruecos en Cadiz.

Barcelona. Encuentro con mujeres migrantes de El Salvador, Siria, Marruecos

Gent. Encuentro con mujeres migrantes de Kurbekistán, Siria, Somalia